Winged Migration

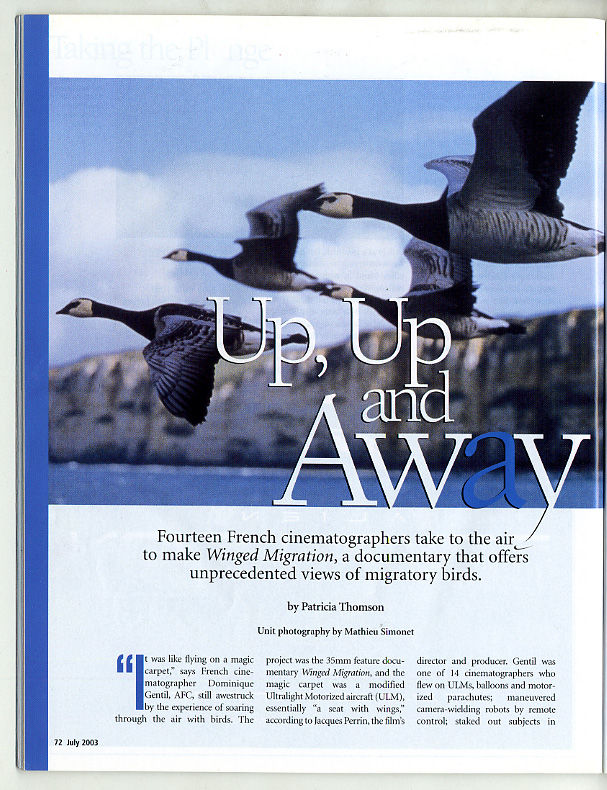

Fourteen French cinematographers take to the air to make Winged Migration, a documentary that offers unprecedented views of migratory birds.

“It was like flying on a magic carpet,” says French cinematographer Dominique Gentil, AFC, still awestruck by his experience soaring through the air with birds. The project was the 35mm feature documentary Winged Migration, and the magic carpet was a modified Ultralight Motorized (ULM) aircraft – essentially “a seat with wings,” according to the film’s director and producer, Jacques Perrin. Gentil was part of a team of 14 cinematographers who flew on ULMs, balloons, and motorized parachutes; maneuvered camera-wielding robots by remote control; staked out their feathered subjects in camouflaged hideouts; hauled collapsible cranes through swamps; and hung onto camera cars, motor boats, and even prosaic dollies while filming 70 species of migratory birds for Winged Migration.

The resulting footage has astonished even veteran bird-watchers like E.J. McAdams, executive director of the New York City Audobon Society. “I’ve never gotten to watch a bird fly from on top of the bird,” he says incredulously. Nor has McAdams flown in formation beside one, close enough to stroke its wing. “Perrin is far ahead of anyone else in that kind of work,” the veteran birder says. “You could see the musculature in the birds’ backs and how they hold their feet when flying; you could watch them landing. For the mechanics of flying, the film was incredible.” So incredible, in fact, that the producers felt it necessary to include a credit line that states “no special effects were used.”

Instead, ingenuity, patience, and serendipity produced these results, helped by an army of 450 enablers, including 17 pilots, legions of ornithologists, animal advisors, and guides, plus the film production personnel. Since migratory birds can cover well over 2000 miles, crossing continents and oceans, the camera teams were running all over the globe. Production took place in 40 countries over seven continents and lasted four years. Total footage topped 300 miles, by Perrin’s estimate.

Not surprisingly, the logistics were Herculean, as indicated by an email executive producer Jean de Tregomain wrote during production. “It was a summary of a normal day’s difficulties,” he explains, “mentioning the future shoot in Vietnam, transport problems in Libya, unusually heavy rains in Kenya and the consequences this would have on filming, a return to the Falkland Islands for a shot essential for the editing, a shoot on the Rhone that had finished successfully with sublime lighting, technical research to film over the forest canopy in Guyana, and spring which was arriving too soon in France and upsetting all the shooting scheduled before the first leaves came out.”

When Perrin started this massive undertaking, he hadn’t a clue whether it would work. “I began with no assurance. I was sure, but I wasn’t sure. But I was sure,” he waffles with a smile. While he had managed to create a cult hit with Microcosmos, his close-up examination of the bug world, precedents for the kind of bird footage he envisionsed were rare as hen’s teeth. The first man to successfully fly with birds was Bill Lishman, a Canadian ULM pilot who in the mid-eighties had hatched some eggs and trained 15 goslings to follow his motorcycle, then an aircraft, using the principles of imprinting first explored by Austrian scientist Konrad Lorenz. (Imprinting is a kind of surrogate parenthood, whereby a newly hatched chick bonds with whatever cooing, nurturing creature first appears before it.) One day Lishman went up with a friend who brought a camera. They sent the footage to Perrin, then host of a French television show. “He made not a documentary, but a document,” Perrin says. But it was enough to plant the seed.

In 1996 Columbia Pictures made a children’s film loosely based on Lishman’s experience, Fly Away Home, but, again, this involved only a dozen Canadian geese. Perrin envisioned something much grander – a film that would explore the mysteries of flight while following the four main axes of migration. The film would tail snow geese, sandhill cranes, and Canadian geese as they fly from North America to southern climates; Eurasian cranes, white storks, swallows, and curlews as they aim for Africa; Siberian cranes and bar-headed geese en route to India; and Southeast Asian knots as they head down to Australia. It would fly with birds over famous settings – the Grand Canyon, Mont Saint Michel, the Twin Towers – and past magnificent landscapes as various as the Sahara desert, the icy Arctic, and Monument Valley. Structurally, the film would follow the cycle of the year. It would include intimate scenes of birds feeding, nesting, coddling their young, and partaking in bizarre mating dances. It would show the life-threatening hazards they face – injury, exhaustion, avalanches, agricultural incursion into nesting areas, industrial pollution, and hunters, both man and birds of prey. To do all this, it would need a storyboard, a guide drafted in close consultation with a professor from France’s Museum of Natural History. “That’s why this film is not completely a documentary,” notes Gentil. “We wanted to provoke some situations.” And, finally, it would be filmed in widescreen 35mm with a minimum of telephoto lenses. The object was to be close up and personal with these familiar yet mysterious creatures.

Jacque Perrin

WHEN ASSEMBLING HIS CINEMATOGRAPHERS, Perrin immediately tapped Thierry Machado, who won France’s César Award for Best Cinematography for Microcosmos and also shot Perrin’s primate documentary, The Monkey People. “He’s the first cinematographer I engaged, because he’s very good, and he’s also physically in good condition,” says the director. “He’s afraid of nothing.” That was critical, since Machado would be the guinea-pig cinematographer, doing test runs in the ULM, parachute, and other vehicles to figure out filming techniques. It took about a year to get things right. “Our technical problems in the first year were nothing compared to learning to fly with the birds,” Machado says. “The difficulty was to be able to fly at the same speed as the birds, remaining in the center of the formation. Our goal was to give the impression of being part of the flight, not just spectators.”

Machado did some tests comparing anamorphic and spherical lenses, and finally settled on 1:85:1 shot full frame. “It seemed to me more interesting for shooting the aerial views,” he says. Next, the technical parameters were laid out for all involved. Since 14 cinematographers ultimately came on board and were shooting separately, “the main problem was having a homogeneous image,” says Gentil, who had previously worked with Perrin on an Ousmane Sembene feature. “So we tried to have some simple rules to get everyone consistent. We had one kind of lens for everybody, one kind of zoom, and only Kodak film stock,” primarily Vision 5246 250D and 5245 50D. There were no filters and rare lights. “We needed the equipment to be very versatile and knew we had to shoot all over the world,” Gentil continues, “so we needed to have equipment we could find everywhere.” All the cinematographers would use an Aaton 35-III or an Arri 3 [Dl3 is incorrect] and work with Zeiss series lenses, with an emphasis on wide-angle primes or zooms that were kept in the 25-50mm range, since Perrin wanted to show always the relationship of the bird to the environment.

Stylistically there were two other guiding principles. Perrin wanted constant camera movement. “When we are in the air, naturally we are always in movement. But when we’re on the ground, I also wanted movement, throughout the documentary,” the director explains. “I wanted the sensation of life. If we’re just fixed, we don’t have that sensation.” More importantly, he wanted his cinematographers to be as close as possible to their subjects. Since wide-angle lenses were prioritized, proximity had to be physical, not just optical. And that brought about some of the cinematographers’ greatest challenges, both in the air and on the ground.

Perrin started with the aerial logistics. While the crew was being assembled, the cast was being hatched and imprinted. Birds don’t normally fly beside aircraft, nor can they be trained like circus animals. So Perrin began what would become the largest imprinting project ever. Over 1,000 eggs – representing 25 species – were raised by ornithologists and students at a base in Normandy where Perrin also rented an airfield. During incubation and early life, the chicks were exposed to the sound of motor engines and the human voice, then were trained to follow the pilot – first on foot, then in the air. These birds would be the main actors, the heroes of flight. The rest of the footage would involve thousands of wild birds, filmed in their natural environments.

Seventy percent of the aerial footage was shot from ULMs, which were tiny enough to follow birds under bridges and down narrow river canyons, and light enough not to fall out of the sky when travelling at the birds’ speed. These were modified to position the extra passenger in front of the pilot rather than behind, placing him on a seat at the end of a five-foot metal plank. “If you saw this machine, you wouldn’t put your best friend on it,” Perrin only half-jokes. But it offered cinematographers an unobstructed 180 degree view.

The Ultralight is so light that it’s easily bounced around by turbulence. The production team worked with a French engineer to devise a stabilizer similar to a Westcam used in helicopters to hold the horizontal line. “But it never functioned well,” the director admits. “After one year, we forgot it. We decided we just needed good cameramen with strong arms.”

Simplification became the film’s mantra. “At the beginning, we didn’t know how to do things, so we were looking to technology for maximum help,” says Gentil. “We worked with electronic people to make a light stabilizer head. Then we built a very sophisticated traveling car with mini-scaffolding to put the camera in multiple places. We tried to adapt the Steadicam on that car. But in the end, we removed all of that and used an ordinary pick-up, attached the camera and operator to be safe, then we did the shot very simply. We understood little by little that the technology was already there, and the best approach was to be as close as possible to the birds.” According to Machado, the Steadicam worked, “but the sensation of flight was not there.” In Gentil’s view, hands-on contact with the camera added to the film’s emotional impact. “When I filmed the birds flying, it was very emotional because I didn’t react through a joystick and wheels to drive my camera, but I used my body. It was more of a conversation.”

The cinematographers flew in other modified aircraft as well, according to the species’ flight patterns and aerological conditions. The second most common vehicle was the parachute, a quiet transport system that could carry two people. The parachutist was rigged with a small motor on his leg to drive the chute sideways. This was handy for birds that ride thermal air currents, such as eagles and storks. On occasion,the cameramen also made use of balloons CUT and, on occasion, model airplanes and model helicopters – better for petite birds and small video cameras (which Perrin is currently utilizing for a television documentary on carrier pigeons).

But rare was the day when all the elements fell into place. Gentil ticks off the challenges: “We had to deal with the birds; are they going to fly or not? We never forced them. We had a real ethic about that. We had to organize the flight with the pilot, ADD: which depended on weather conditions. After that, we had to bring the birds to the site we wanted filmed: Monument Valley, Mont Saint Michel, the Eiffel Tower, all those places. We had a precise script and we had to fly over a precise place. Then we needed to have good light conditions and stability of the air when we fly.” (Fortunately, birds prefer to fly in the cool morning air and at the magic hour.) “There were so many conditions, to have all of them together was very rare. Sometimes we spent three months getting one shot.”

All the cinematographers who flew with the birds – Sylvie Carcedo, Luc Drion, Laurent Fleutot, Bernard Lutic, Stephane Martin, Fabrice Moindrot, plus Machado and Gentil – came away profoundly moved by the experience. Gentil recalls flying so close he had to push the birds away. “They were sometimes a foot away. The wing was on the lens.” When flying under the best conditions, he says, “I cried sometimes, it was such a big emotion.” He remembers the day he flew over Mont Saint Michel, capturing an exquisitely beautiful image of the famed island-city far below the barnacle geese formation. “It was the day the birds climbed 2,500 to 3,000 feet high – the highest we’d ever flown. We were alone – the pilot, birds, and I alone in the sky – and I was getting something very, very strong for the film – and for us personally also.”

For Machado, the first time it all came together was in Iceland. That day the wind had finally calmed down, and he was preparing to fly alongside a huge glacier. Take off was perfect, the birds fell into formation around the aircraft, and they gradually found an altitude at which the birds were confident. “As if my magic, I put the camera on my shoulder, the flight was completely stable, the birds had decided to co-operate. Far below the crevasses sped by: all my good resolutions were forgotten, and we were now flying over the glacier, right in the middle,” a much more dangerous flight path. But Machado was elated. “For the first time after a year and a half, we had the impression that the camera became a bird.” And that footage produced the first compliments from the Paris office. That mission, says Machado, “gave the tone of the movie for the aerial views.”

THE WILD BIRDS, IN TURN, ENTAILED A DIFFERENT SET OF CHALLENGES and a different group of cinematographers. In addition to Machado, there was Michael Benjamin, Laurent Charbonnier, Philippe Garguil, Ernst Sasse, Michael Terrasse, and Thierry Thomas. Some had vast experience shooting nature films, such as Charbonnier, an early hire who had shot over 30 nature documentaries. All used Winged Migration’s standard equipment package: an Aaton and Arri, the Zeiss lenses, plus Charbonnier brought along a 25/250 Angenieux zoom and a 150/600 Canon zoom.

But some of the most important accoutrements were more likely to be found in a bird sanctuary than a camera store. “Perrin’s aversion to long lenses was a problem for birds that were difficult to approach,” says Charbonnier, “so we had to be clever and create some blinds, then have a long wait in order to get our actors at a good distance.” These ‘blinds’ – places of concealment designed for watching birds or animals – were constructed out of canvas then camouflaged with leaves, wood, or other materials picked up from the spot.

When Charbonnier was in Nebraska on a feeding ground of 70,000 Canadian geese, for instance, Perrin wanted a shot of the birds waking up very early in the morning. Typically, the geese ate in the fields during the day, then flew back to the river to spend the night. “If the team arrived at night with all their material,” Charbonnier relates, “we would have disturbed and scared the 70,000 geese. The only solution was come to the river while the geese were away eating and install a blind on a sunny spot in the middle of their arrival area.” So while the birds were gone, they dug a large hole in the sand and camouflaged a blind, oriented towards the east for their preferred camera angle. Charbonnier took his position at three in the afternoon, then waited. “I spent the night in the blind, which was a little damp (we napped until the dampness won. The next morning there was fantastic light, and I was in the middle of 70,000 geese, the closest less than 11 feet from the lens! All the geese left to eat at 9:30, and I waited until they were gone before calling my assistant to come rescue me. The scene was done in two hours, but it entailed location scouting, preparation, a night of dampness and patience. It’s a very good example of our [method] for many sequences in the film.”

Other equipment ranged from the crude to the high-tech. To follow sea birds as they plummeted to the Arctic ocean from their nests high on a cliff, Machado attached his camera to a kind of bungee cord, using 200 meters of elastic and wood stabilizing wings to keep the camera from spinning when it hit bottom. At the other end of the scale was a three-wheeled robot “like a moon machines,” says Perrin. As Carbonnier relates, “I asked Perrin and his director of production to build a robot in August 1999, after we shot some waders in Germany who were very aggressive.” When Charbonnier shot the waders in Mauritania a few months later, he came with the robot. It held an Aaton on an external arm for shooting the birds, and a video camera to view its path. The camera operator stood about 500 meters away with a monitor, guiding the robot and adjusting the zoom and iris by remote control. Often the robot was camouflaged. “The birds sometimes came up and looked right into the lens,” says Perrin. “Some of the shots were very amusing.” Charlonnier was pleased as well. “In the three weeks spent in the National Park of Banc d’Arguin, [Philippe Garguil and I] were able to shoot spectacular footage of thousands of birds [...]

The filmmakers also used a lightweight crane that could be carried by hand and assembled in six minutes, as well as a variety of floating platforms. “We spend half of the film in water,” says Gentil. “Birds never go to easy places; they’re always far from roads, or in wetlands or mud.”

But no one complained—at least, not too much. “These are movies that one isn’t always happy to do because they are so long and laborious,” says Machado. “But one is always proud to have shot them.” (In fact, some of the Winged Migration cinematographers have already reteamed with Perrin for an Imax film on bird flight, which is being created for the French theme park Futuroscope.)

Making Winged Migration gave many of the cinematographers [...] friends. “It changed my life,” says Gentil with a laugh. “I’m now very aware of the cry of the bird. I’ve seen birds migrating over Paris, looking for a stop for the night, and I never used to notice that. Now in my little garden in Paris, I feed them during the winter. I finished the film two years ago, but it was a very intense experience. I was close to the human dream, to fly with birds.”

Published in the July 2003 issue of American Cinematographer.